IRISH CHURCH & CIVIL PARISHES - THE DIFFERENCE

- irishfamilydetective

- May 8, 2018

- 9 min read

Updated: Jan 15, 2021

Introduction

Genealogy has its own similar version of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. The four pillars of genealogy are Census Records 1901 and 1911, Civil Registration, Church Records and Land Records. However, unlike Maslow’s hierarchy, any pillar of the genealogical sphere becomes a basic need dependent on the premise that ‘the only absolute rule in family history research is that you should start from what you know, and use that to find out more.’[1]

Whilst a full government census was taken every ten years from 1821, the only surviving Irish census records which are available for research purposes are for the years 1901 and 1911. The records for 1821 to 1851 were destroyed by fire at the Public Records Office in 1922 and those for 1861 to 1891 were destroyed prior to 1922 by order of the government. Land records are useful as a census substitute; however, they in essence only provide a guide to the residence of the head of family, the property occupied and property owner. Civil Registration began in 1845 with the registration of non-Roman Catholic marriages only. In 1864, all births, deaths and marriages were registered. Prior to this period, parish registers may provide the key to unlocking the genealogical past.

Church Records - In Context

In 1536, the Irish Parliament declared King Henry VIII head of the Church of Ireland. Consequently, the parish landscape changed, whilst the Church of Ireland became the state church, and retained the existing parish structures, the Roman Catholic Church created larger parishes due to the constrictions imposed on it as result of the reformation and because of population change. In County Wicklow, there are twenty-one Roman Catholic parishes compared to fifty-seven Civil Parishes (Fig.1 & 2). ‘Therefore civil parishes – the geographical basis of early censuses, tax records and land surveys – are almost identical to Church of Ireland parishes.’[2]

Figure 1: County Wicklow Roman Catholic Parishes.

Figure 2: County Wicklow Civil/Church of Ireland Parishes.

Although the parish structures were different, both Roman Catholic and Church of Ireland dioceses were quite similar in the past as both were derived from the Synod of Ráith Breasail in 1111, whereby ‘a scheme was introduced dividing the country into two ecclesiastical provinces, Armagh and Cashel, each with twelve suffragan sees.’[3] The Synod of Kells, 1152 divided the two provinces to become four, whilst retaining the existing dioceses. In 2016, the Roman Catholic Church retains the principles of the synod, in that it comprises of four archdioceses and twenty-two dioceses (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Current Roman Catholic Diocese Structure.

The Synod of Drogheda in 1614 recommended that parish clergy have a baptismal font and a book to record baptismal and marriage entries, however no registers survive. In 1670, the Synod of Irish Bishops went one-step forward and ordered clergy to keep baptism and marriage registers. Only registers for Wexford town and St. Nicholas, Galway survive. In 1697, the banishment of Roman Catholic bishops and clergy meant record keeping dissipated. During the first decade of the eighteenth century, religious persecution intensified. ‘In 1703 the Penal Laws, forbidding Catholics to keep registers, were enacted.’[4] In addition, the registration of Catholic priests were ordered and decreed that ‘only one priest could be registered for each civil parish; all others were obliged to leave the country.’[5]

Penal Laws relaxed in the first half of the eighteenth century and due to growing tolerance, record keeping began again, principally in urban areas, more so in the Munster and Leinster. The reason for this province variation is that many of the priests trained in continental seminaries were based in Leinster and Munster and had been trained extensively including record keeping. The Roman Catholic Church became relatively stable when Catholic Emancipation began in 1829 repealing Penal Laws.

Roman Catholics made up the majority of the population in Ireland, in 1841; they constituted 80.9% of the population. The established church accounted for 10.7%, whilst the remaining, Presbyterians and other Protestant Dissenters made up the remaining 8.4%. By 1871, Roman Catholics remained the largest denomination although numbers had fallen according to the census of that year; this is probably because of the famine. As expected the majority of the established church lived in Ulster in 1871 at 58.4% whilst only 5.3% living in Connaught.

Roman Catholic Parish Baptismal Registers

The parish priest is the custodian of his parish records and nearly all registers are held in the parishes of their origin. Entries in registers are generally in chronological order by date. This may not be the case if the parish had more than one priest. The commencement of Roman Catholic baptismal registers varies wildly in the four provinces. Of all baptismal records, '30% of those in the province of Leinster, and 11% of those in Munster, began baptismal record keeping before 1800. The comparable figure is only 3% in Connaught and Ulster’.[6] Baptismal registers in most cases contain the following information:

Date of baptism

Child’s name

Father’s name

Mother’s name

Names of sponsors

Name of priest

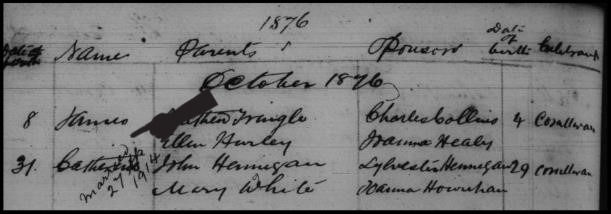

In some cases, the townland of the family is also recorded. Baptisms are recorded in ‘either Latin or English – never in Irish’. Baptisms took place within days of the child’s birth, and up to the mid-nineteenth century were held in private residences. After the Synod of Thurles 1850, ‘the celebration of the sacraments of marriage and baptism in private residences was forbidden and was normally restricted to churches. Marriage and baptismal registers were mandated for every parish.’[7] By the early 1900s, many ‘Catholic priests made marginal notes next to specific baptismal records, to make a note where someone born in the parish married outside of the home diocese, usually overseas’ and in addition on occasion the subsequent marriage of a child is noted.[8] (Fig. 4)

Figure 4: Baptismal Register, Catherine Hennigan, 1876, noting date of marriage, Dunmanway Baptismal Register.

The baptism of Peig Sayers (Fig. 5) shows the Latin version of Margaret, Margareta, her parents, godparents, the townland in which the family reside, Vicarstown, as well as the name of the priest who carried out the baptism.

Figure 5: Baptism of Peig Sayers, Ballyferriter Parish, 29 March 1873.

In the 1860s customised books with printed column headings were commonly used. My great-grand aunt’s baptismal record in 1871 (Fig. 6) is a dramatic improvement when contrasted with my great-great-grandfather’s entry fifty years earlier in 1821 (Fig. 7).

Figure 6: Kate Kelly, 21 May 1871 Bantry Baptismal Register.

Figure 7: John Connell, 20 September 1821 Glanmire Baptismal Register.

Roman Catholic Parish Marriage Registers

Catholic marriages were not permitted to take place during the forty days prior to Easter (Lent) nor during the four weeks preceding Christmas (Advent) unless a dispensation was granted. Dispensations were also required when blood relations married. My maternal ancestor Michael White married Mary Murray and got special dispensation due to the fact they were third cousins (Fig. 8)

Figure 8: Marriage Michael White and Mary Murray, 9 February 1836 Dunmanway Register .

Figure 9: Lord Dungarvan's marriage entry Pro Cathedral register 10 March 1828 (no other entries on the page).

Generally, the following information was recorded in the registers:

Date of marriage

Names of persons marrying

Names of witnesses

Townland

Other information that may be included possibly in the later registers (Fig. 10):

Residence/Eorum Residentia

Occupations

Ages

Parent’s names/Nomina Parentum

Parent’s Address

Names of witnesses/Testes Adfuerunt

Witnesses’ Address

Figure 10: 1903 Marriage Entry St. Mary's Pro Cathedral.

Roman Catholic Parish Burial Registers

Due to the persecution of Roman Catholics during the penal times, there are a large number of Catholic burial entries in Church of Ireland parish records. However, Roman Catholic burial records are quite spartan, ‘out of 1042 parishes whose registers have been microfilmed by the National Library of Ireland, only 214 have been found to have kept burial records.’[9] In addition, the majority of these records commence in the 1800s, 'a general survey of the burial records now available shows that only 29 parishes have burial records from the 18th century, mainly in Meath (9 parishes) and Westmeath (7 parishes).’[10] This is probably due to Bishop Patrick Plunkett who admonished the priests of his diocese, Meath, for being lacklustre in keeping records of sacraments.

Burial Registers in Munster are not plentiful; this is possibly due to a regulation issued by the Bishops of Munster in 1808, requesting registers of baptism and marriage to be regularly kept by all parish priest, however no mention is made of burial records.

Generally, the following information was recorded in the burial registers:

Date of burial

Names of deceased

Townland of deceased

An extract from the Dunboyne burial register for January 4 1791 shows the burial of Christopher Kelly (Fig. 11). A burial register from the same parish in 1865 is even more difficult to read with inkblots and spidery writing (Fig. 12).

Figure 11: Dunboyne Roman Catholic burial register 1791.

Figure 12: Dunboyne Burial Register, 1865.

Church of Ireland Parish Baptismal Registers

Church of Ireland records generally start much earlier than Roman Catholic records as from the 1560s it was the Irish State Church. However, disaster struck when a fire in the Public Records office in 1922 destroyed the majority of registers. The Parochial Records Act declared that baptismal and burial records prior to 1871 and marriage records prior to 31 March 1845 should become public records, which is why they were stored in the Four Courts. Thankfully, a further amendment was inserted which allowed records to remain in local custody, providing the parish had adequate safekeeping facilities, thereby saving many records. Records from 1 January 1871 were held locally and unaffected by the fire.

Baptismal registers supply at a minimum:

Date of baptism

Child’s name

Father and mother’s name

Officiating Clergyman

In addition, on some occasions the following is recorded:

Residence of the parents

Father's occupation

Figure 13: Oscar Wilde, Baptismal Record, St. Marks Church of Ireland Parish, 1855.

Church of Ireland Parish Marriage Registers

After 1845, when non Roman-Catholic marriages were recorded by the state, marriage records contain all the information contained in the civil registration records, including:

Location and date of marriage

Date of marriage

Name, surname, age, previous marital status and residence of bridal party

Father’s names and occupations

Witnesses

Officiating Clergyman

Figure 14: Church of Ireland Marriage 1851 Earl of Howth (Widower) & Henrietta Barfoot, signed ‘Howth’ by the Groom

Church of Ireland Parish Burial Registers

Even though Church of Ireland burial records are more plentiful, their content is not very extensive. Like Roman Catholic records, information includes (Fig.15):

Date of burial

Name of deceased

Townland

In addition, some records also include the age of the deceased, which may not be accurate.

Figure 15: Burial of the "Hanging Judge", Earl Norbury, John Toler, Great Denmark St., 1 August 1831.

Other Religious Entities Registers

Presbyterian

The Presbyterian Church came primarily to Ulster from Scotland in the 1600s but like the Roman Catholic Church, it faced a similar persecution due to the Penal Laws. Presbyterian registers hold the same information as recorded by the Church of Ireland. However, Presbyterian records commence much later, in most cases, from the nineteenth century. Although, where a strong community existed, chiefly in Ulster, records begin in the eighteenth century. After 1845, Presbyterian marriage records contain all the information that is recorded in the civil records.

Methodist

The Methodist Church was formed in 1747, when John Wesley first arrived in Ireland. The Church remained part of the established church and so therefore did not face the prosecution other Protestant dissenters experienced. In 1816, the movement split, whereby Primitive Methodists remained within the Church of Ireland and the Wesleyan Methodists became independent. Methodist records, dated between 1747 and 1816 can be found in Church of Ireland registers.

Quaker

The difference between Quakers and the other religions is that the sacrament of baptism is not performed. That does not however mean births were not recorded. The Quakers came to Ireland in the seventeenth century from Leicestershire, England. ‘George Fox, the founder of the Society, advised every meeting to keep a record of its business and also to keep registers of births, marriages and burials. The records are very complete and for most monthly meetings they exist almost continuously from the date of origin.’[11]

Conclusion

‘It is no mere antiquarian interest which attaches to these records. Their safe-custody is a matter of practical importance, not to any one class of the people only, but to all classes. Every individual be he rich or poor, peer or peasant, has an interest in the preservation of our Old Parish Registers; but to the poor man, of whose existence they constitute almost the only record, it is of special consequence to preserve intact.’[12]

Thomas Taswell-Langmead surely sums up how important Parish Registers are to the historical timelines of our country. The registers have proved their significance in the past in legal and peerage questions and they certainly will retain their worth in the future for the wealth of information they hold.

Unfortunately, due to religious persecution and ignorance, there are many gaps in records. In addition, there is a divide between rural and urban registers. Thankfully, with the advent of technology, remaining records are now far more accessible and the combination of microfilm and digital archives has ensured that these family history building blocks are retained for future generations.

Sources:

[1] John Grenham, Tracing Your Irish Ancestors (Dublin, 2012), p. xxi

[2] Grenham, Tracing Your Irish Ancestors, p. 35

[3] Tomás Ó Fiaich, ‘The Primacy in the Irish Church’, Seanchas Armahacha: Journal of the Armagh Diocesan Historical Society, Vol. 21, No.1 (2006), p. 2

[4] Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Irish county maps showing the locations of churches in Munster province (Salt Lake City, 1977) p. 5

[5] Henry A. Jefferies, ‘In spite of dungeon, fire and sword: penal days in Clogher’, History Ireland, Vol. 17, no. 3 (May – June, 2009), p. 18

[6] James G. Ryan ed., Irish Church Records: their history, availability and use in family and local history research, (Dublin, 1992) p. 114

[7] Ciarán O’Carroll, ‘Pius IX’ in James Corkery and Thomas Worcester (Eds.), ‘The Papacy since 1500: From Italian Prince to Universal Pastor’, (Cambridge, 2010), p. 139

[8] Fiona Fitzsimons, ‘Catholic Parish Registers’, History Ireland Vol. 23, no. 2 (March – April, 2015), p. 21 h World War 1 raging.

[9] Patrick J. Corish and David Sheehy, ‘Records of the Catholic Church’, (Dublin, 2001), p. 38

[10] Ryan (ed.), Irish Church Records: their history, availability and use in family and local history research, p. 131

[11] Department of Culture, Arts and Leisure, ‘An Irish Genealogical Source, A guide to Church Records’, (Northern Ireland, 2011), p. 39

[12] T.P. Taswell-Langmead, Parish Registers: A plea for their preservation, (London, 1872), p. 7

Comentários