The daughter of Dr. Cummins, Professor of Medicine at UCC, Iris’ individuality began on the day she was born in 1894. Her mother was thrown from a side-car when a horse bolted and, as a result, went into premature labour. Her father ordered that the newly-born Irish be bathed in champagne![1]

Early Life

The eighth of eleven children, Iris Ashley Cummins was born at 17 Saint Patrick's Place, Cork, on 4 June 1894 to Dr William Edward Ashley Cummins and Jane Constable (née Hall).[2] William Ashley Cummins, the eldest son of Dr William Jackson Cummins, was appointed Professor of the Practice of Medicine at University College Cork (UCC) in 1897. The family legacy endured, as four of his children – Robert, Mary, Nicholas and Jane – followed in his footsteps and pursued successful medical careers.[3]

Although born in Cork City, Iris spent her formative years at Woodville, near Glanmire, the countryside retreat of the Cummins family. It is here that she resided on the night of 31 March 1901 and is recorded on the Irish census, with her mother, Jane, five siblings (later the family grew with five more children born to the couple), along with a governess, nurses and servants, while her father was resident at Patrick’s Place.[6]

The governess, Winifred Holloway, instructed Iris and her sisters as their mother, Jane, apparently did not approve of further education for women.[8] However, Iris was not to be deterred, and along with her sisters Mary and Jane attended Queen’s College, Cork (UCC). During her time at UCC she also edited the Journal of the Engineering Society. In 1915, Iris graduated as Bachelor of Engineering, with honours, becoming the second female to graduate in engineering in Ireland and the first from Cork.[9]

Sportswoman

Iris was not only intellectually gifted but also displayed considerable prowess as a sportswoman; in 1909, aged just fifteen, she won a place on the Irish ladies’ hockey team. Her international career continued for much of her life, giving her opportunities for travel that few Irish women enjoyed, culminating in her captaincy of the Irish ladies’ team tour of the USA in 1925, where she and her teammates were presented to President Calvin Coolidge at the White House. At this time, she was President of the Irish Hockey Union (Hockey Ireland) from 1923 to 1925.

The Great War

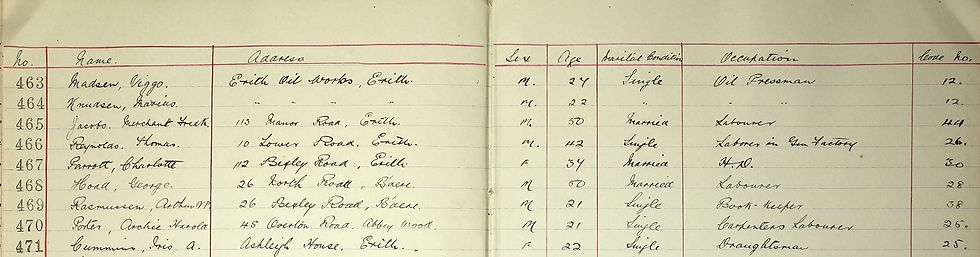

Iris’ graduation coincided with technological advances in warfare, allowing her to use her engineering degree immediately when she joined the World War 1 effort. She worked at the Royal Arsenal’s munitions factory at Woolwich in London, the Vickers factory in Erith, the Royal Naval Dockyard Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, Scotland and the Admiralty Department in Haulbowline Dockyard in Cork, gaining significant experience previously unheard of for women.[12]

Back to Ireland

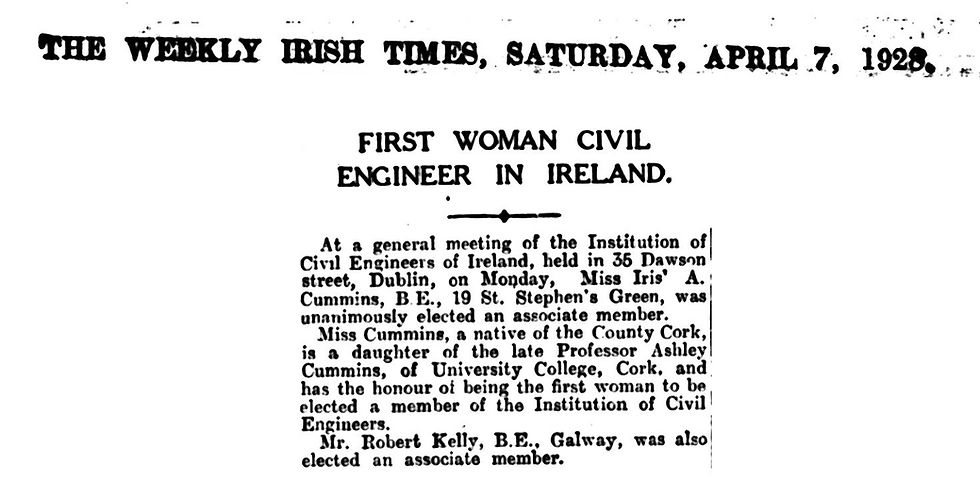

Following the end of the Great War, Iris returned to Ireland and began her own private practice in Ireland, however, this appears to have been less than successful, perhaps a sign of the time, given her sex and religion. It would appear, as a member of a prominent Church of Ireland family, her opportunities were limited. Nevertheless, resolute in her determination, Iris was appointed as a surveyor on the outdoor staff of the Irish Land Commission, the first time a woman had received such a post.[14] In this same year, she became the first female associate member of the Institute of Civil Engineers in Ireland, she continued working and writing, eventually retiring in 1954. In 1928 The Weekly Irish Times pronounced the ‘First Woman Civil Engineer in Ireland’ when at a general meeting of the Institution of Civil Engineers in Ireland had unanimously elected her as an associate member, thereby she has the honour of being the first woman elected to membership.[15]

Death and legacy

The death, in Dublin on 30 April 1968, of Iris Cummins, B.E., Woodville, Glanmire was announced in the Cork Examiner, she is buried in Saint Lappan’s Graveyard, Little Island, Cork.[16] In 2022, University College Cork named its civil engineering building after Iris, the first time a campus building was named for a female. UCC President John O’Halloran rather aptly summed up Iris Cummins: ‘she was an independent and creative thinker whose pioneering actions challenged the gender norms of her day. We are proud of her achievements, and hope that everyone who passes through the doors of the Iris Ashley Cummins building will find inspiration in her legacy.’[17]

[1] Cork Examiner, 18 February 1986.

[2] Copy of birth certificate for Iris Ashley Cummins, 4 June 1894.

https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/churchrecords/images/birth_returns/births_1893/02298/1862017.pdf (accessed 6 April 20247 July 2022).

[3] The British Medical Journal, vol. 2, no. 3278 (October 1923), p. 788.

[4] www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai000565996/ (accessed 6 April 20247 July 2022).

[5] Evening Echo, 20 April 1972.

[6] Cummins family, 1901 census return, NAI, www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai001856777/, http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/reels/nai000513490 (accessed 30 September 2023); Richard J. Hodges and W. T. Pike, Cork and County Cork in the twentieth century and Contemporary Biographies (Brighton, 1911), p. 184.

[7] www.myhome.ie/residential/brochure/woodville-house-woodville-glanmire-cork/4396651 (accessed 6 April 2023).

[8] Margaret Ó h Ógartaigh, ‘Women Engineers in early 20th century Ireland’, The Engineers Journal, vol. 56, no. 10 (December 2002), p. 49.

[10] Image courtesy of University College Cork.

[11] UCC Official Gazette, Vol. 4 No 12 (June 1914).

[12] Westminster Gazette, 5 March 1927.

[13] Bexley World War I registration cards. Bexley Local Studies & Archive Centre, Bexleyheath,

Kent, England.

[14] Birmingham Gazette, 5 March 1927.

[15] The Weekly Irish Times, 7 April 1928.

[16] Cork Examiner, 1 May 1968.

[17] Irish Examiner, 23 February 2022.

[18] Image courtesy of Historic Graves.

Comments